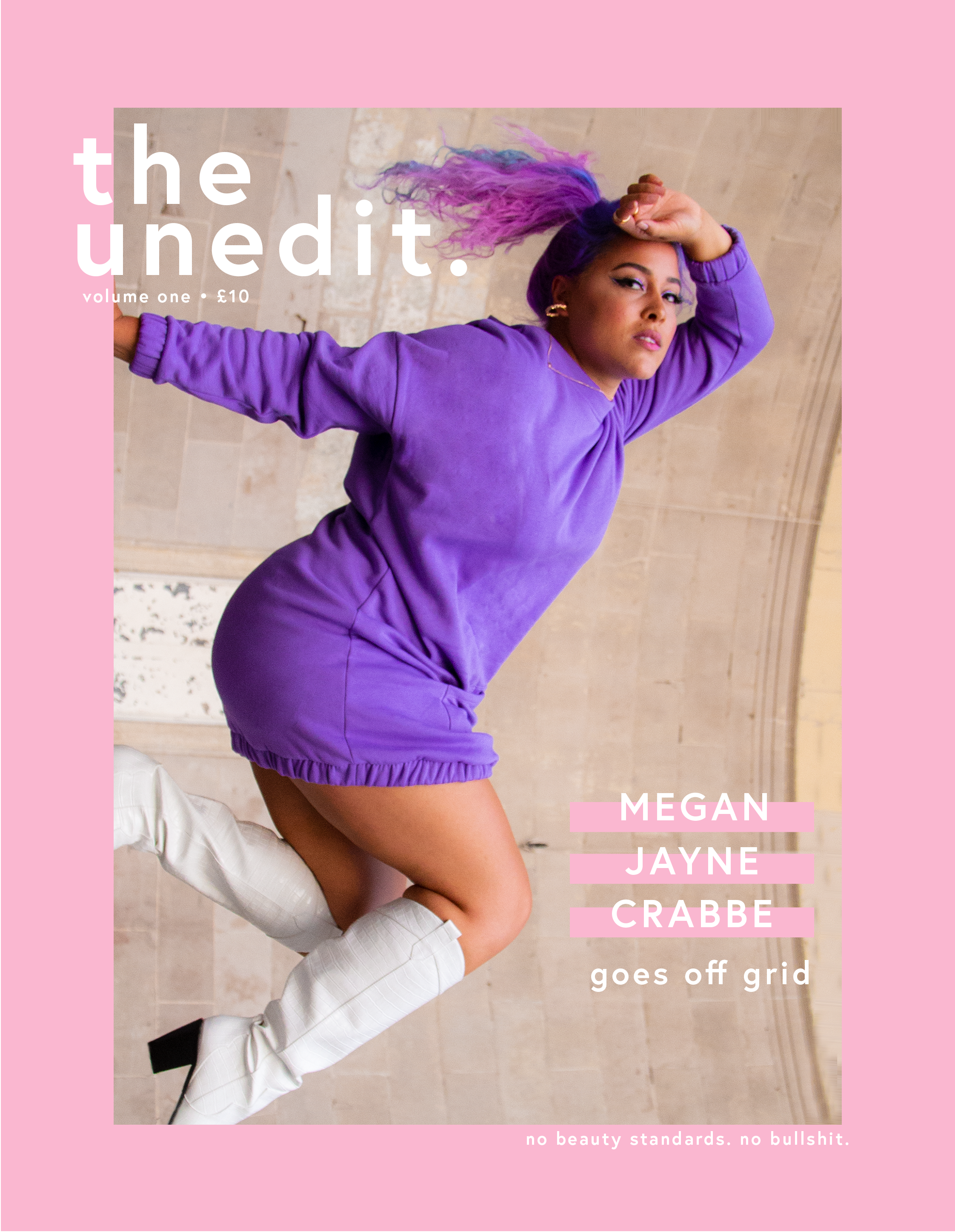

Let's Not Prematurely Celebrate: Women In The Media Still Have A Long Way To Go

Trying to pin-point the various changes in the way women have been represented in the media is tricky. On the one hand, we now see more diversity in terms of body size, ethnicity, class, and so on – but on the other, women continue to be held to unattainably high standards. I worry that too much emphasis has been put on the success of progressive steps such as body positivity, creating the illusion of a changed narrative. There is a real danger that by celebrating prematurely, we risk people assuming the goal has been achieved, when in reality, women continue to be boiled down to their looks and ridiculed for almost everything they do. Coverage of Adele’s weight loss earlier this year demonstrates this. Despite winning nine Brit Awards, 15 Grammy Awards, five American Music Awards, a Golden Globe and an Academy Award, according to the British media, losing weight is the ultimate goal that Adele has finally achieved. Only now can she be deemed a true success; a slim, white, successful woman. What we all dream to be, right? Wrong! This coverage has fuelled the fight against the thin ideal and reminded us that while changes are apparent, they are still stuck at a superficial level.

The death of Caroline Flack is still raw. Painted as an abuser and hounded for months on end, before taking her own life. Instantly, the press narrative changed to celebrating the incredible woman she was, subsequently neglecting the role they played in her death. Had Flack been a man accused of assaulting his partner, I can’t help but wonder how long the media onslaught would have lasted.

The treatment of Meghan Markle is an example of the embedded racism in the UK, we’ve all seen countless comparisons of how differently she was portrayed in the press to Kate Middleton. The accusations were constant, saying that Meghan was doing things for attention, like cradling her baby bump regularly, or breaking tradition and tarnishing the reputation of the Royal family. The Black Lives Matter movement and other Black activists are working tirelessly, shedding an exigent light on the systemic racism in this country, so perhaps we’ll begin to see publications reflecting on their negative portrayal of the former royal and acknowledging their responsibility in the struggle she faced living here.

More recently, Stephanie Yeboah, author of Fattily Ever After, called out sports brand Adidas for a plus-size clothing campaign featuring Maya Jama, a British television presenter, able-bodied and largely considered as slim and beautiful. The campaign calls for a celebration of all shapes and sizes but choosing to support the narrative of the thin ideal, whilst implying that Maya Jama’s body is ‘plus-size’ sends an incredibly dangerous message. It is yet another example of a brand playing into the body positivity movement, while denying representation to the people it was created for – people who already lack media representation. With the average woman in the UK a size 16, this campaign shows we clearly still have work to do to reduce the harm done by the media promoting a false image of ‘acceptably fat’.

I have spent the past nine months researching whether the media has a responsibility to represent realistic bodies, conducting a survey and a series of interviews with media professionals. While a definite answer is hard to find when discussing media responsibility, my research highlighted a contradiction between what audiences want and what media outlets want to offer. Yes, we are seeing an increase in diversity in the media, but the question is whether it is evolving because audiences are vocalising what they want, or because editors are recognising that the landscape is changing. The Kate Moss era of fashion magazines is thankfully in the past – when eating disorders were glamourised and the final edited products looked like Barbie doll replicas – but image editing still remains integrated in the British media.

Slim, white women have been the ‘ideal’ for decades, the ultimate standard of beauty that we should all be aspiring to. Forgetting just for a second the notorious lack of diversity; the ‘ideal woman’ pushed on to readers in the UK, was more often than not, physically completely unattainable, even for other white women. Digital retouching has given us the ability to alter real bodies to look ‘perfect’ and create dangerously unrealistic versions of women; fake bodies that are viewed as aspirational.

Within the survey, 97% of participants stated that they would prefer to see unedited, natural pictures of women in media:

“Photoshop can lead to a negative self-perception and insecurities, as well as fuelling an unhealthy idea of what is considered beautiful.”

“Being exposed to these unrealistic and often fake images of perfectly smooth skin and gorgeous figures (which don’t represent real life) means that when individuals look at their own bodies, with scars, cellulite etc… they feel abnormal. When really, they represent true beauty.”

The media industry is just that – an industry – and like any other, it relies on sales and profits to keep churning out content. This creates a balancing act between printing content that sells notoriously well, such as gossip and unrealistic lifestyles, and content based on celebrating women and their natural bodies. Magazines in the UK have been criticised in the past for jumping on the bandwagon without being committed to the cause. Katie Meehan, an Instagram influencer who was born with a facial disfigurement, uses her platform to promote her knowledge that she is beautiful, despite not fitting into the mould that was made for women in this country. She referred to magazines such as Take A Break and Chat, saying that she has been featured on numerous occasions, when they praised her bravery and what she stands for, while promoting dieting and playing on readers insecurities throughout the rest of the issue. This supports further survey findings with 83% of participants believing magazines can cause harm to their readers in the form of body dissatisfaction and poor mental health. Featuring progressive content is futile if a publication continues to be part of the problem in every other way. Katie talked about the challenges she faced as a young woman:

“My worth was based on what I was going to look like. Doctors always told my parents, ‘she’s not going to be pretty’, or ‘she might not be beautiful’. Nobody ever spoke about the quality of life that I’d have or whether or not I’d get a good quality education.”

Social media has given Katie a platform to voice her story and encourage others to accept themselves despite the constant barrage of negative information. She’s just one example of an alternative message in the era of user generated content, challenging traditional forms of news by demonstrating real and attainable lifestyles.

With this change in mind, it is hard to identify whether we would have seen the same progress in terms of diversity if social media hadn’t existed to apply pressure. Magazines appear to base their editorial decisions more on what will benefit the brand and generate income rather than on the reality that the reader wants to see. An anonymous interviewee suggests that women’s magazines exist as a fantasy and to enforce regulation forcing all publications to adhere to realistic content would completely alter the products. Using Vogue as an example, a fashion magazine that fills its pages with advertorials and designer brands. For most women, this is not their reality, but if they stopped including designer clothes and beautifully attractive ideals, would it still be Vogue? This is what we have to consider before we can expect to see any permanent change. If we can separate fantasy and reality, then maybe there is room for both narratives.

Based on this, I would suggest that the few changes we do see have come as a result of audiences and women encouraging discussion to change the way we are portrayed. Accelerated by social media, this new wave of body positivity is an incredible example of a network of strong women who know their worth is based on more than just their weight. Recognised as an emerging trend, the movement has been co-opted, and oftentimes watered own and monetised heavily by the media. We have to remain vigilant to recognise when someone is preaching because they believe in representation, or merely announcing their allyship to sell copies.

Until women experience equal and diverse representation, we can’t relax and assume anything more will happen. We aim to reach a point where all people are treated the same; regardless of gender, race, ability, sexual orientation, weight… the list goes on.

Progress is being made. Highlighting the issue and encouraging conversation is one way to keep the spotlight on the UK media, and provides opportunity to call them out when they revert back to the narrow narrative of the thin ideal. I think we will continue to see change at the hands of audiences. With so much honest and inspirational content available across print and online mediums, we won’t continue to tolerate unrealistic representations of women. We don’t want to feel guilty for not meeting societal beauty standards; for having cellulite, body hair and stomach rolls. I don’t want to see magazine covers criticising women for taking so long to lose the baby weight or for ‘letting themselves go’ in a new relationship, as though these are things to be ashamed of.

Women were once portrayed as housewives, expected to cook and behave accordingly. Then there was a shift to sexualising the female form, where our appearance was our most valuable asset. Whilst we’re still overly sexualised, we are living in a revolution where women are fighting to be seen as real people. Not idolised as the perfect wife, a sex object to admire, a successful career woman, to name only a few of the narratives that are pushed on us. Even despite this millennial shift, we haven’t reached our goal. We still have a long way to go before we beat the narratives and stop having impossible standards imposed on us. I urge you not to become complacent.