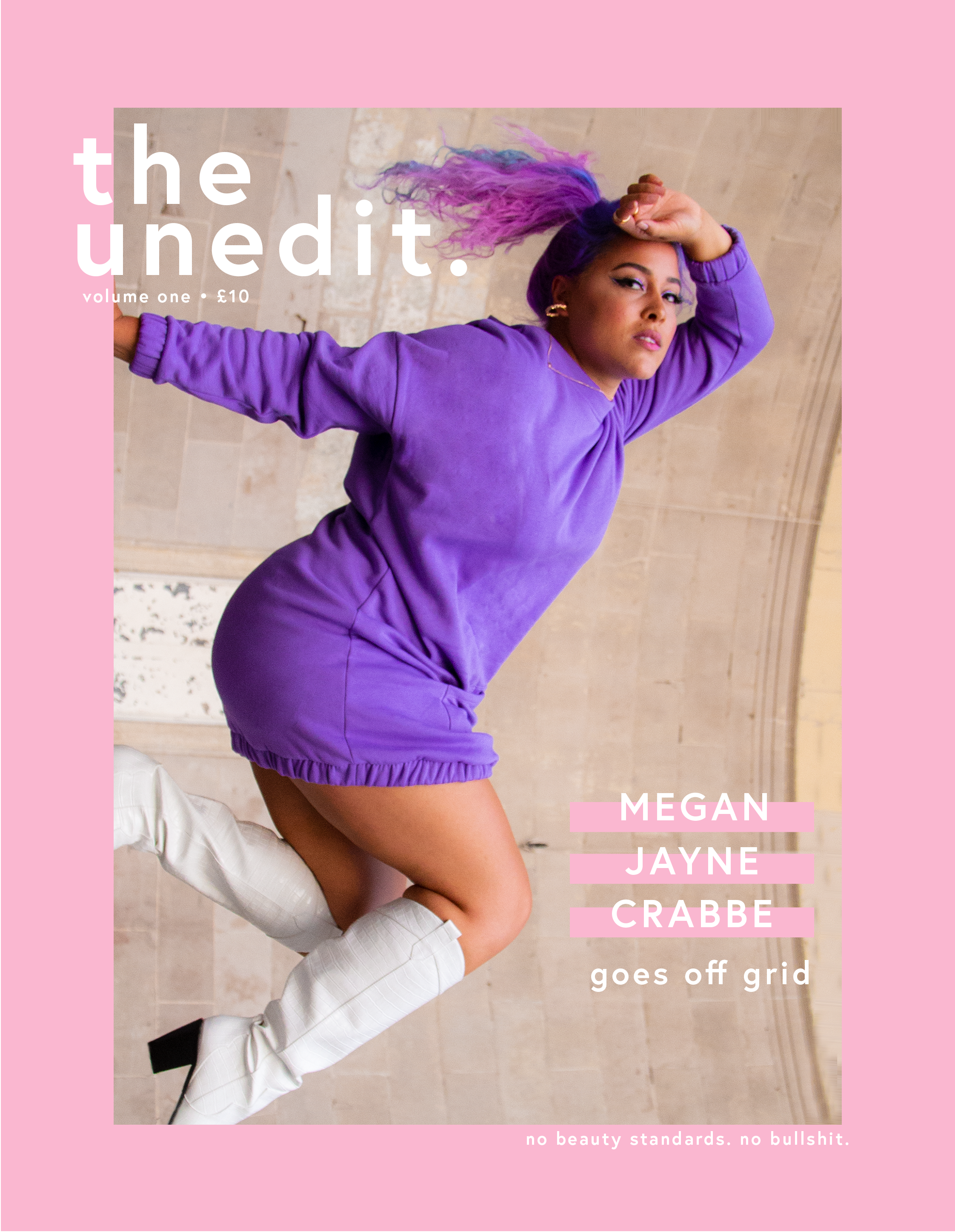

These Amazing Women Have Learnt To Love Their Post-Mastectomy Bodies

October marks Breast Cancer Awareness Month, and with one person being diagnosed every 10 minutes, we at The Unedit feel that it’s important to offer the right information and guidance. That’s why this October we’re working in support of Breast Cancer Care, the only specialist UK-wide support charity for people affected by breast cancer. Each week, we’ll be bringing you articles with the help of the charity’s specialists, to do our part in raising awareness.

When it comes to fighting breast cancer, treatment can vary in type and intensity based on the individual and what’s best for them. Understandably so, the whole experience can be gruelling and extremely overwhelming, and as an additional precaution, for many, surgery is an option to help reduce the likelihood of the cancer returning. However, in a world where there’s a tonne of pressure to fit certain body ideals, especially for women, the idea of a mastectomy — the removal of the breast tissue — can be a daunting one, leaving many unsure of how their future body will look. Even those who don’t undergo mastectomies, even lumpectomies — which remove the cancer, but keep as much of the breast as possible — and aggressive chemotherapy can find themselves grappling with their self-confidence as their body changes and reacts to treatment. With mastectomies reducing the chances of secondary breast cancer by 99%, it’s a life-saving decision to make. We had the pleasure of speaking with three women who each underwent a double mastectomy with reconstruction. Each with different stories, they shared with us the ups and downs they’ve had with their bodies.

Sonia Bhandal, 30, is from Feltham, Middlesex and works in Marketing and Communications for a local Hospice that provides end of life care. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2016, when she was 28 years old, and had a double mastectomy in 2017. Prior to her surgery, Sonia went through chemotherapy for four months, during which, Sonia tested positive for the BRCA2 gene. The genetic mutation was something she’d inherited from her mum, who sadly passed away from breast cancer after six years of fighting the disease when Sonia was only 14 years old. With this increasing her chances of her cancer returning, she chose a bilateral (double) mastectomy over a lumpectomy to significantly lower the risk.

Image courtesy of Sonia Bhandal

Gemma Whelan, 26, lives outside of Edinburgh, Scotland and works in the Financial Services industry. She underwent a double mastectomy after discovering she carried the faulty BRCA gene, passed down from her mum who had fought breast cancer twice, initially diagnosed aged 38. Her great-grandmother had passed away as a result of ovarian cancer, which is directly linked to breast cancer, and Gemma took the genealogy test following on from her mum being found positive for the gene.

Image courtesy of Gemma Whelan

Liz Williams, 25, is from Southend, Essex, and works in Insurance. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014 after finding a lump, when she was just 21 years old. Liz’s treatment started with a lumpectomy to remove the cancer, followed by fertility treatment to have her eggs frozen, then chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Carrying on from that, she started monthly injections to halt oestrogen production, and currently takes medication, something that she will continue to do so for the next six years. Liz’s diagnosis at such a young age allowed her to be offered a genealogy test, which came back positive for the BRCA1 gene mutation. With a 65% chance of her breast cancer returning, she opted for a double mastectomy.

Image courtesy of Liz Williams

Talking about her relationship with her body pre-diagnosis, Sonia says: “I disliked my body. I would complain about being chubby, not liking my stomach, I would feel my breasts were saggy (even though they weren’t), I would get paranoid of little dark scars on my legs. If anyone took a picture of me, I would immediately hate it. If anyone complimented me, I would disregard the compliment or say something negative about myself in response.”

Before the surgery, Gemma found that she didn’t struggle with her body as much. “Before finding out about the gene, I’d say I’d always had an okay relationship with my body. Like a lot of women, I did often think, I’d love if I looked like this, or I’d love to lose a few pounds. However, I wasn’t someone who overthought about little imperfections.”

Liz found herself somewhere between the two, having lost a large amount of weight shortly before her breast cancer diagnosis. “I had a mixed relationship with my body. Due to my weight loss, I was feeling quite confident, despite the usual niggles of wishing my stomach was flatter, or that my arms were thinner. I’d had issues with health anxiety for many years, so I regularly checked myself for lumps and bumps.”

For Sonia and Liz, breast cancer treatment affected their body image in different ways.

“I began to appreciate what I had before — hair, eyelashes, eyebrows, glow in my skin tone. I became very grey after chemo,” says Sonia.

Image courtesy of Sonia Bhandal

Image courtesy of Liz Williams

Liz lost faith in her body in another way: “After I was diagnosed, I felt extremely betrayed by my body, like it had let me down and I couldn’t trust it anymore. Each hospital appointment I attended, we would talk about my body and my cancer and I would feel like it wasn’t me that they were talking about. I had taken my clothes off in front of so many people for various tests and checks, that I just became detached from it, my breasts specifically. I found that I stopped worrying about my weight and whether my tummy was flat or not, mainly because I had much bigger fish to fry. I remember, when I was diagnosed, wondering whether I would lose weight, but due to the hormonal side of breast cancer treatment, this wasn’t the case.”

“Despite all this, I did have a new-found confidence within myself; I loved wearing wigs and I spent ages practising drawing my eyebrows back on and applying fake eyelashes. I think it just gave me time to escape from the reality of everything.”

Whilst it didn’t deter any of them from going ahead with their double mastectomies, adding to the general anxieties of surgery, societal pressures, ideals and expectations did bring extra worry to Sonia, Gemma, and Liz.

“I was scared, very scared,” Sonia says. “I cried, I mourned by breasts. I was so stressed as I felt my boyfriend at the time wouldn’t be attracted to me any more. I had all the irrational thoughts possible. Unfortunately, I didn’t have time to get therapy like some BRCA gene carriers do before they decide to have a surgery, as my situation had to be dealt with urgently. However I would recommend that anyone who has the option to get therapy before having a bilateral mastectomy should! It will help prepare for all the body changes.”

“[Societal pressure had an impact] to some degree, as I couldn’t imagine having a bilateral mastectomy without reconstruction. My boyfriend at the time was very supportive as I was scared about having a hip-to-hip scar (due to the nature of the procedure), and he turned to me and said, ‘Have you thought about not having reconstruction at all, and just having your breasts removed?’ It meant the world to me. But as I was so young and my relationship wasn’t set in stone, I couldn’t have imagined not having breasts. I see women on social media who have bilateral mastectomies without reconstruction and they are absolutely stunning. I think the media can have a huge effect on you and that’s why you need to make sure you’re making the right decision for you, not for society, not for your partner — no one but you.”

“Society’s notion that your breasts ‘make you a woman’ didn’t influence my decision because I didn’t feel I had a choice,” says Gemma. “It did, however, make me fear the outcome even more, and I did think the surgery would make me feel less of a woman. I thought I’d never be able to look beautiful without my clothes on.”

For Liz, she had some time to think before the operation: “There was about a year gap between me deciding to have the surgery and actually having it — it gave me plenty of time to think about the potential risks, but I was always confident that I still wanted to go ahead with it. I spoke to my surgeon many times about the potential outcomes and read online on the Breast Cancer Care website about what to expect, how they would look after the surgery and what would happen if it was to fail.”

“I had always been quite fond of my breasts; I liked the size, the shape and placement. One of my main concerns about the surgery was that when I woke up, they wouldn’t be a similar size to what they were before, or that they would be wonky or misshapen. I was petrified that the surgery wouldn’t be a success and that I would wake up and the reconstruction would have failed and I would be flat. However, my fears that the cancer would return was much stronger and I know that it was something that I had to do for my mental wellbeing. I also eventually realised that as much as I liked my breasts, that preventing a reoccurrence should be more of a concern to me than whether or not they’d be identical in size and shape after surgery.”

Physically, the recovery from surgery was difficult for all three women, but after encountering “everything that could have gone wrong”, Sonia ended up critically ill in hospital for six weeks. Her life-changing DIEP flap reconstruction surgery — where they take the fat from your stomach to reconstruct the breasts — became a life-threatening time, finding herself in the less-than 1% category that experienced infections, wound breakdowns, and more after surgery. Eight surgeries later, including one to reconstruct her abdominal wall, Sonia was able to go home.

Adjusting to a new body is easy for no one, and recovery is more than just physical, but the mental and emotional aspects of coping.

“It was so hard adjusting, especially as my boyfriend at the time broke up with me a few months after my bilateral mastectomy and went off with another woman,” says Sonia. “I’m sure it had nothing to do with my surgeries, but when you’ve just had a major surgery like that, you question if it’s because of your scars, or the fact that you have no nipples, or whether he isn’t attracted to you anymore. The hardest part was having no nipples. This is still a touchy subject for me and I’ve only just started speaking about it. After surgery, I looked back at old pictures that I used to hate and now looked at them in awe, wishing I could be that girl again. And in that moment, I realised that I need to appreciate who I am today, as tomorrow is never promised, and your body is constantly changing. I realised I needed to love myself, not just focus on my external attributes. I became a lot more confident in who I am, rather than what I look like, and this overall made me a much more confident person.”

“It took me a very long time after surgery to adapt to my new body,” says Gemma. “I’d say it probably took me a good 18 months to accept what I had to live with. The day after my surgery, my surgeon came to see how I was getting on. He lifted my hands and told me to hold and touch my new breasts. I didn’t want to do it, but I knew exactly why he was getting me to. I’ll never forget that moment and I’m so grateful to him now for encouraging it. It wasn’t until I got home about a week later that I forced myself to stand in front of the mirror. I was black and blue all over and my breasts were red and swollen. The scars were still covered with the dressings so I couldn’t see how they looked. I was so emotional and so exhausted that I didn’t have the energy to cry any more. I remember thinking to myself, what have I done to my body? and I so badly wished I could turn back the clock and have my old breasts back.”

“Even though I was really happy with my reconstructions once the swelling and bruising had gone, I spent a lot of the first year comparing them to one another — taking photos and keeping records of what they looked like, as I was so worried that they may change over time,” says Liz. "This worry carried on until she decided enough was enough. “About a year after surgery, I realised how obsessive it had become and how much stress it was causing me, and I decided to just delete all of the photos. I haven’t taken another since.”

In an effort to rebuild her confidence after she’d “hit complete rock bottom”, Sonia focused on a 30 Things To Do Before 30 list, where she’d complete things such as eating in a restaurant alone, climbing the O2 Arena, committing to six months of counselling, and making new memories with her body.

Image courtesy of Sonia Bhandal | Photo credit: Taylor Oakes Productions

“I felt so much more confident,” she says. “What I looked like and my scars took a back seat and I began to love me, internally. As much as I’m still insecure about not having any nipples, or my scars, I’m also so much more confident. I’m more outspoken, more of a go-getter, and I don’t get as shy or nervous when it comes to work or social situations. Part of my new list, 12 Things To Do When 30, was to have a naked photoshoot to capture my mastectomy scars. Getting naked and bearing all would’ve been hard for the pre-cancer me, let alone the me with no nipples and covered in scars. But I did it, and it was so liberating. I have accepted the no-nipple me, which means that I’m feeling more positive about my next stage: nipple reconstruction.”

Now, Sonia, Gemma, and Liz are all living their cancer-free lives with the new bodies that helped save them.

“I’m still insecure [about my scars and not having nipples],” Sonia says. “However, I’ve realised confidence is key. If I portray confidence, if I feel confident in who I am as a person and the fact that my body cannot define me, then that’s all that matters. I am proud of my scars. I am proud that I survived cancer. I am proud I made a decision to reduce my risk as a BRCA2 gene carrier. I’m proud I didn’t give up when I was critically ill in that hospital bed. My scars are reminders of all that I’m proud of. My breast do not define my femininity. I do. I didn’t love my body pre-cancer, I didn’t love it during cancer, so I am most definitely not going to waste any more time.”

Image courtesy of Sonia Bhandal

“It’ll be three years in January since my surgery and I have a good relationship with my body now,” says Gemma. “I don’t take it for granted any more, and I’m grateful for what I have. I’m pleased with my reconstruction, and although I’d still love to have my old breasts back, I’ve accepted my new ones. When I look in the mirror and see the scars, sometimes I still feel sad that I’ve had to do this to my body, but I also feel proud. And as strange as it may sound, I’ve grown very protective over my breasts, as if somehow if I’m not careful, I might break them! Since the surgery, I have more respect for my body and I accept that this is me, and this is what I look like. Since becoming a volunteer for Breast Cancer Care, I’ve had the opportunity to meet and speak with some amazing women who also carry a faulty gene and some women who have had to battle breast cancer. Hearing other people’s stories makes me realise just how lucky I was, and I feel more and more grateful every day that I’m living a normal life.”

Image courtesy of Gemma Whelan

Image courtesy of Gemma Whelan

“My diagnosis left me quite anxious about my health,” says Liz. “And despite my surgery, I still find that I want to check my breasts for lumps just in case. I had nipple reconstructions at the end of 2017 and recently had them tattooed to make them look more realistic. They aren’t the same as before, they aren’t identical in shape and size, they feel different and have scars, but I’m really happy with them and I think that they look amazing. My maintenance drugs make it hard for me to lose weight again, so I’m not as thin as I’d like to be, but I’m alive. I find it hard to trust myself when it comes to my body and illness, but I think given what I’ve been through that it’s only natural to feel worried about it — I’m currently attending counselling.”

Image courtesy of Liz Williams

Each of these women have been through more in their lifetime than many, and it’s safe to say that there have been lessons learned: gratitude for life, doing only what’s best for you, accepting and loving your body regardless of how it looks, and taking absolutely nothing for granted. Additionally, Liz’s diagnosis at such a young age is proof that there’s no such thing as “too young”. “Do not be deceived by age,” Liz says. “Cancer is often thought of as an older person’s disease, but it’s not. Cancer doesn’t care how old you are — it doesn’t discriminate. Although getting breast cancer at a young age is rare, it isn’t impossible and it’s important to check your breasts for changes. The more often you check, the more you will get to know your breasts and what’s normal for you. It only takes a minute and it could save your life.”

We asked each of them if they had any advice for other women out there who may be struggling to accept their body, either during breast cancer treatment, or post-surgery.

“Focus on all the positive things about yourself, write it down on a piece of paper, and stick it up on your mirror,” says Sonia. “Write down every single compliment you can ever remember receiving. Read it and believe it. I also found that therapy really helped me in accepting my new body. Don’t get me wrong, I’m still on a self-love journey and I’m not 100% confident with my scars etc, but you get there slowly by taking the right steps.”

“In the early days of my recovery and even now when I find myself having an off day, I think, why me? Why did I have to go through this? I take a step back and remember exactly why I did this and what the potential alternative would’ve been for me if I didn’t choose to have surgery,” says Gemma. “I’d encourage other women struggling to do the same. You might not feel perfect, but you should feel proud of everything you’ve achieved, mentally and physically.’”

“Cancer causes your body to change in ways that you don’t even think of,” Liz says. “When I was diagnosed, I was so worried about my hair falling out, that it didn’t even occur to me that I would lose my eyelashes and eyebrows, too. My advice would be that during treatment, most of the changes are temporary and will reverse, so try and find a way to make you feel better about you. I ended up with a collection of 14 wigs and I absolutely loved trying out new hairstyles and colours, just because I could! I think the thing to remember post-surgery is that the changes are hard and they do take a while to come to terms with, but at the end of the day, they are changes that will help you survive. Also, the Breast Cancer Care app, BECCA, is really helpful to help find ways to accept yourself and move on from your diagnosis.”

The Unedit would like to thank Sonia Bhandal, Gemma Whelan, and Liz Williams for taking the time to talk to us and share their stories for our readers, and the team at Breast Cancer Care for their wonderful support to help create this month’s content for Breast Cancer Awareness Month.

For care, support and information, call Breast Cancer Care’s nurses for free on 0808 800 6000 or visit www.breastcancercare.org.uk.